What can be said about the heralded dystopian masterpiece A CLOCKWORK ORANGE (1971), adapted from ANTHONY BURGESS’S book ‘A CLOCKWORK ORANGE’, by the cinematic giant STANLEY KUBRICK, that’s not been said before? Countless articles and a handful of academic books have already analyzed the subjects of free will and corruption by the hand of the Law, religious themes, and brainwashing effects, even the notorious scandal that forced Kubrick to withdraw the film from British distribution. Nonetheless, Kubrick’s cinematic achievement has many enigmatic layers, which entice adventurous explorations. Many have the opinion that Kubrick faithfully adapted the book from the words to the screen, but only a few see that

‘Kubrick has two advantages that Burgess lacks in his novel: images and sound’. (McDougal, 2003, 13)

Although the film is fairly straightforward, Kubrick changed the main idea of the book in the transition to the film in his usually very distinctive and subtle ways. The whole film is eccentric, but it’s undeniable that

‘… its style and narrative structure keep the spectator in a position of awed conviction, distant and involved, amused and horrified, convinced and querulous, and at every moment involved’. (Kolker, 2003., 27)

In the popular movie database website IMDB the plot of the film is described as:

Let’s begin with the notion that the movie isn’t set in the future.

The newspaper the main character’s father is holding in his hand has a date printed in one of the articles; it says ‘August 1970’. The year of the setting was located in the past, since the movie officially premiered on the 2nd February 1972. By examining the given premises of the film, many things don’t add up to the overall picture. The movie is mostly described as a crime film or a vicious drama that is layered with sci-fi elements. Although the film can be analyzed

‘as a crime film, A Clockwork Orange has all the elements of one’, (Chandna, 2006., 69)

when looking at the narrative, the visual and metaphorical aspects, we can see that they are really the ones that control the film structure. Also, for a film that is a mixed bag of these ‘serious’ genres, there is an enormous amount of comedy involved. Many of the scenes are satirical and these funny bits are so comical that they undermine the violence and the torture, which the movie should be trying to present as a serious matter. Why would Kubrick consciously decide to go down this road? He decisively told everyone who asked that

‘It’s all in the plot’.

Stanley Kubrick (1972, 13)

In this analysis, some specific aspects of the plot will be examined to clarify the overall theme of the film.

UNEXPECTED CONNECTIONS

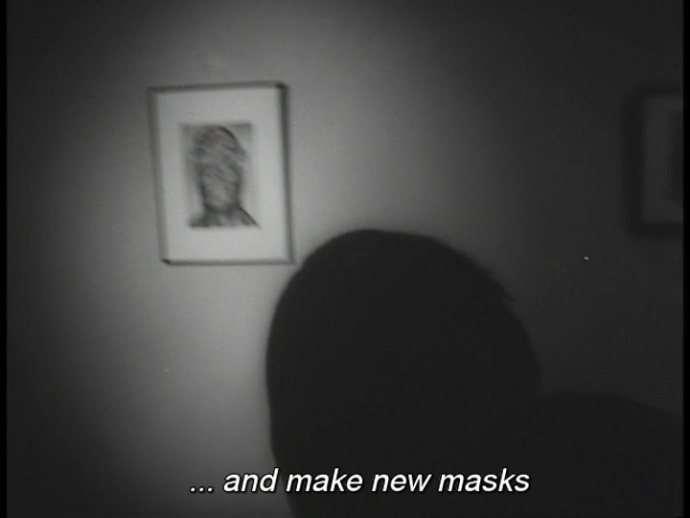

Kubrick never officially commented anything on the underground masterpiece Funeral Parade of Roses (TOSHIO MATSUMOTO, 1969), but some elements are directly taken from the film because they are too specific to just be a coincidence. The following similarities are:

- The quote in the opening of Funeral Parade of Roses, although directly connected to the plot of Eddie, also explains the faith of the main character in A Clockwork Orange. He is a torturer but gets tortured himself by the Law and stripped of free will.

- Eddie, the main character in Funeral Parade of Roses, wears fake eyelashes because he is a transvestite. The main character in A Clockwork Orange isn’t a transvestite, but wears only one fake eyelash. His three droogs also have transvestite features: one wears the other fake eyelash and the other two wear red lipstick on their lips.

- For a flashback Matsumoto used a fisheye lens to communicate an awkward moment from the past. In Kubrick’s Clockwork, a fisheye lens is used to express the horrific experience the writer has to endure.

- In the first one, Eddie hides in an underground gallery. By looking at the exhibition of weird faces, he faints. To express the moment of losing control the camera spins into the air and lands on the floor. Kubrick used the same trick to show the point of view of the main character as he jumps through a window.

- Eddie, in FPOR, has a fight with the Lady of the Bar he’s working in. The sequence is sped up and accompanied by the music called William Tell Overture. The same music and effect of the sped-up footage is used in ACO during the main character’s orgy scene.

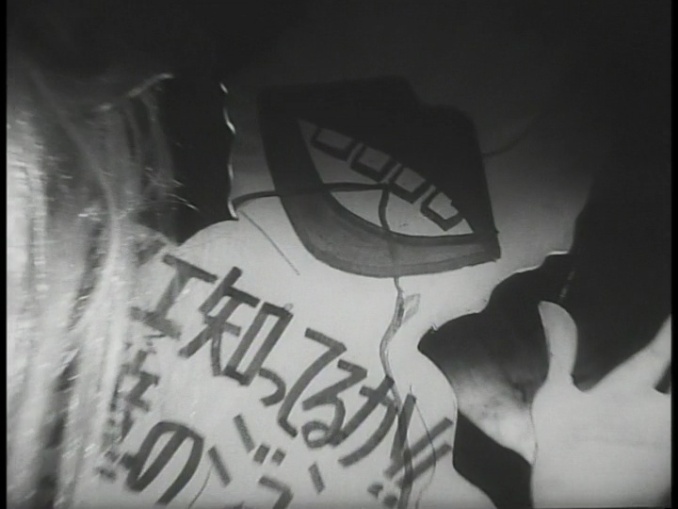

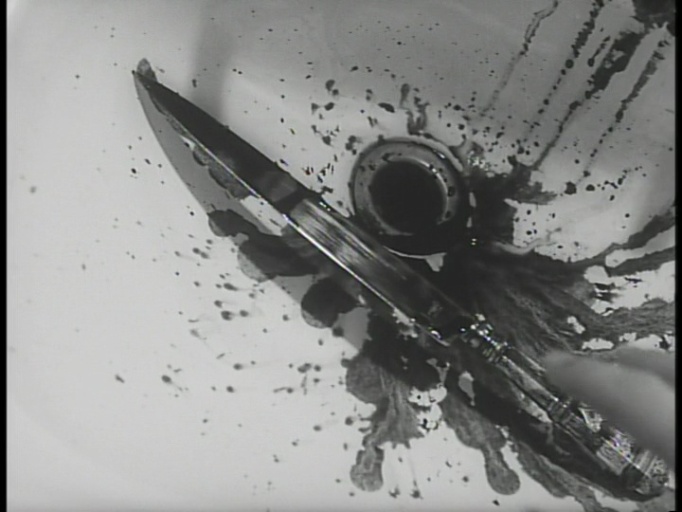

- During a party scene, in FPOR, graffiti depicting lips and some teeth is fairly visible because the camera zooms in so fast to cling to them. The same effect happens in ACO in the scene where the main character kills the Cat Lady. The camera also zooms in on the lips of a painting.

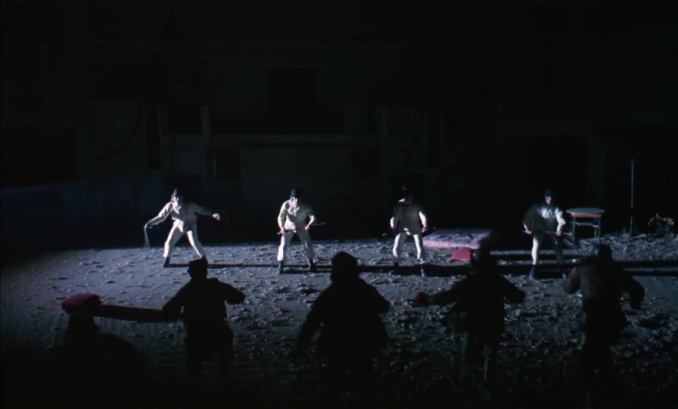

- In the Japanese film two rival gangs get into a fight, just as two gangs get into a fight in A Clockwork Orange.

- Both movies are also connected through the theme of suicide. Both main characters try to end their life of suffering.

Although Kubrick used eight clearly specific details from Funeral Parade of Roses, the main themes of the films couldn’t be more different. The first one is about hypocrisy in underground gay clubs, and the second one is about the manipulation by the government. Why would Kubrick refer to a movie unlike his own? If he’d make a homage to any number of movies, would it work just as well? Or maybe not? Distinctly

‘for Matsumoto, the ethical is aesthetic and the aesthetic here is rendered ethical by being intentionally superficial. Camp aesthetics redefine the relations of the nuclear family as role-playing, self-stylization, and dramatic presentation’. (Sinnerbrink, Trahair, 2016., 7)

The way Burgess’s book handles the heavy violence and the rigid characters wasn’t what Kubrick had in mind. Kubrick was interested in something else. To convey his visionary idea, he needed the camp aesthetics to explain a different idea from the book.

BETWEEN LIGHT AND SHADOW

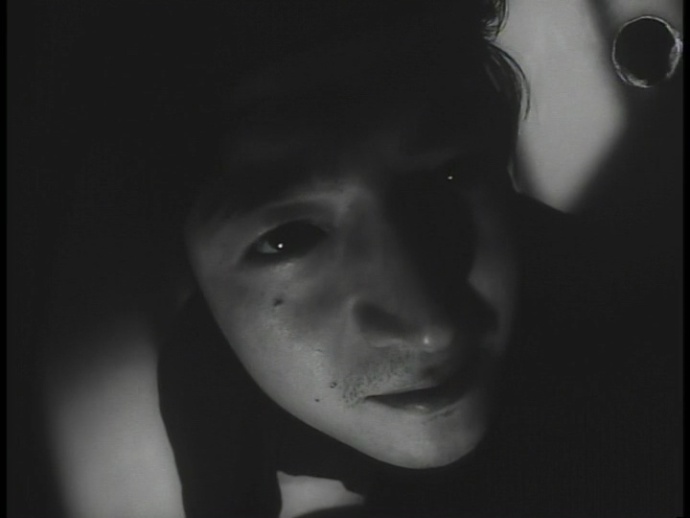

There are plenty of German cultural references inside A Clockwork Orange. Most notably, the frequent use of Nazi symbols, the music of Ludwig Van Beethoven, and many characteristics of the German Expressionist Movement are also incorporated.

Although some of these cues are barely noticeable for average audiences, they certainly are visually striking when

‘Kubrick appropriated expressionist techniques in, for example, the stark backlighting of the early scene in which little Alex and his droogs first encounter the singing tramp, as well as in the jerky camera and rapid montage of images when Alex smashes the face of the Cat Lady’. (Gabbard, Sharma, 2003., 87)

More of the expressionist characteristics include:

- CHIAROSCURO LIGHTING – The stark contrast between light and shadow was used mostly in Film Noirs to highlight the duality of the characters. If the scenes aren’t depicted with razor-sharp edges,

‘for the most part, Expressionist films used simple lighting from the front and sides illuminating the scene flatly and evenly to stress the links between the figures and the decor’. (Bordwell, Thompson, 2003., 108)

- MIRRORS AND GLASS – Another characteristic used in Expressionism is the connection to glass. Mirrors are reflections of the soul, glass can shatter like the personality of the characters and

‘In German films, windows, glazed doors and puddles can also act as mirrors. […] Life is merely a kind of concave mirror projecting inconsistent figures’. (Eisner, 1952, 130)

- ABSTRACTIONISM – Expressionism shows how

‘The laws of perspective, faithfulness to anatomy, natural appearances and colors counted for little to nothing; distortion and exaggeration became an equivalent for rendering the material world transparent to the psyche’. (Wolf, 2004., 9)

Simply put, the interior emotional states of the character are visibly reflected in the exterior world. That’s why Alex’s feminized eye

‘… metonymically links him to the female furniture. Furthermore, the white shirts and pants both he and his droogs wear as part of their costume parallel and blend in with the porcelain white female furniture-figures upon which they sit’. (De Rosia, 2003., 67)

Barbara Walker cited Pauline Keal who said that the film has

‘an attitude that is ugly, loud and brutal toward the female human being: all of the woman are portrayed as caricatures; the violence committed upon them is comically; the most striking aspects of the decor relate to the female form’. (Walker, 1972, 4)

Pauline Keal has rightly observed that the characters are one-dimensional, but it’s not only the female characters, it’s the male characters as well. Unfortunately, she failed to explain why the movie portrays them as such.

‘In A Clockwork Orange, many of the performances are highly stylized, especially the late scenes with Patrick Magee that prompted Pauline Keal to suggest that the actor was auditioning for a future in horror movies’ (Gabbard, Sharma, 2003., 105)

but in reality, Kubrick encouraged actors to play their characters in an over-the-top manner. When examining the film, actors act unrealistically, their character’s motivations are completely unclear, no one’s delivering any back-story and they speak in an invented language like they are inside a theater production, complete with bright wigs and distinct word accentuation, but this

‘… Expressionist acting was deliberately exaggerated to match the style of the setting’. (Bordwell, Thompson, 2003., 107)

The setting Bordwell is talking about is the external representation of the main character’s psyche. The world according to him is a cold, devastated, amoral society, which tries to manipulate everyone, even the psychopaths. But what is important to notice is that

‘The exaggerated fragmented actions are not only theatrical, but also invoke the idea of fantasy’. (Fallsetto, 1994.)

In the end, it becomes abundantly clear

‘A Clockwork Orange is an antirealistic film’, (Kolkner, 2003., 29) a ‘blatant cinematic parody’, (Rice, 2008., 65)

and everything comes back down to the character of Alex.

THE CHARACTER OF ALEX

‘The sadistic gang leader’, as IMDB describes him, is named Alex (MALCOLM MCDOWELL). He is an underage, drug-fueled, egoistic maniac that finds relaxation in beating up homeless people, raping women, killing women, stealing cars, and listening to his favorite music by Ludwig Van Beethoven. As the narrator of the movie, he has a soothing voice that guides the spectator through the pits and downfalls of his persona, so the audience takes his words for granted. Spectators assume Alex is telling the truth, but Alex is an unreliable narrator.

‘Kubrick called Alex ‘a creature of the id”, (Rice, 2008., 52)

because he is driven by his primal impulses, which exist without the suffocating borders of morality. Established as a liar, a killer, and a psychopath, he is unusually intelligent and there is no apparent rationality that Alex can employ when explaining his story, but

‘The viewer will experience the events of the film as Alex experiences them’. (McDougal, 2003., 14)

Why is it so essential that the audience needs to plug into the point-of-view of Alex? Kubrick decided to utilize the outrage of the camp aesthetic, and combine it with the expressionist visual style and the made-up nadsat language because it perfectly captures the fantasy; the completely made-up world, and unrealistic characters that exist only in Alex’s thoughts. Anthony Burgess summarized it best when he said

‘Clockwork Oranges don’t exist.’

Anthony Burgess (Burgess, 1986.)

The biggest clue that the film is a fantasy played out in Alex’s mind is given in the first shot of the movie. Namely, Alex’s ghastly close-up shot, breaking the fourth wall barrier with his intense stare and heavy breathing, followed by a tracking shot to reveal the location around him, thus explaining visually that the audience will see a movie from his point-of-view and that he bids you welcome to his world. It’s not so obvious at first, but

‘Alex is quite clear about his status as a fictional character. One reason for his unflagging irony is due not only to the fact that he knows how things will work out but also because he knows that he has been endowed by his creator with a sharp consciousness of his own MISE-EN-SCENE and his existence as fiction’. (Kolker, 2003., 31)

THE DEPTHS OF ALEX’S FABRICATION

When examined, details seem to arise that are either too coincidental or the complete opposite, some are subtle jokes, and others don’t even make sense. ‘Alex’ manipulated basically everything inside the movie.

- ALEX’S NAME

According to the website http://www.sheknows.com the name Alex is a Greek name, which means: Defender of man, protector of mankind. Since Alex in the movie is presented as a psychotic maniac and a murderer, how could Burgess give him the name that implies something so positive? Although the character makes only wrong decisions throughout the movie, he is used as a stand-in, to demonstrate an example of what not to do, and he shows what will happen to you if you act like him. Also, notice that

‘In Kubrick’s script Alex has two names: Alexander de Large and Alex Burgess. In the novel ‘Alexander de Large’ is used only once, when the narrator alludes to his phallic size after the ménage a trios’. (Rice, 2008., 60)

Alexander de Large is his alias, but his real name was printed in the newspaper; Alex Burgess. In the scene where Alex is being processed before going to prison, the Chief Guard (MICHAEL BATES) asks him:

Chief Guard: Name?

Alex: Alexander de Large.

Chief Guard: You are now in H. M. Prison Parkmoor. From this moment, you will address all prison officers as ‘sir’. Name?

Alex: Alexander de Large, sir.

Chief Guard: Sentence?

Alex: 14 years, sir.

Chief Guard: Right. (Kubrick, 1971)

The evidence that the whole movie is played out in Alex’s head is proven once more. Alex identifies himself with his alias, but the Chief Guard accepts it as his real name. There is no possibility that in reality, the Chief Guard would accidentally accept his fake name since he is holding an official document in his hand where Alex’s real name is written. He gives the impression of a determined and loyal worker, an outstanding reflection of an employee following protocol. Furthermore,

‘…the most basic of these [cinematic rules] is the 180-degree rule or ‘axis of action’ […] the axis creates consistent screen direction’, (Bordwell, 2011.)

since everything in the film is not what it seems, the consistent 180-degree rule is broken in this scene, explicitly stating that Alex and the Chief Guard are on the same side or the same person. This whole sequence doesn’t exist in the book, so it’s inserted by Kubrick into the movie for a specific reason. Alex has an enormous ego, so his name has to be pretentious, and fake, a name for a self-proclaimed leader which also needs to imply his extraordinary courage.

It’s no coincidence that Alex dresses completely in white and wears a round bowl hat because subconsciously he thinks of himself to be as impeccable as the giant penis statute he encountered at the Cat Lady’s house. He uses the giant penis statue to kill the Cat Lady because he usually uses his genitals as a weapon, as evidenced when raping the writer’s wife.

- CONNECTIONS TO OTHER CHARACTERS

The characters he meets during the movie are somehow connected to Alex. Either he owns things they own, or he wears the same clothes or they are connected visually. Through these connections, it is implied that Alex and the others are not only sharing a bond, but they are one and the same person, or products of his imagination.

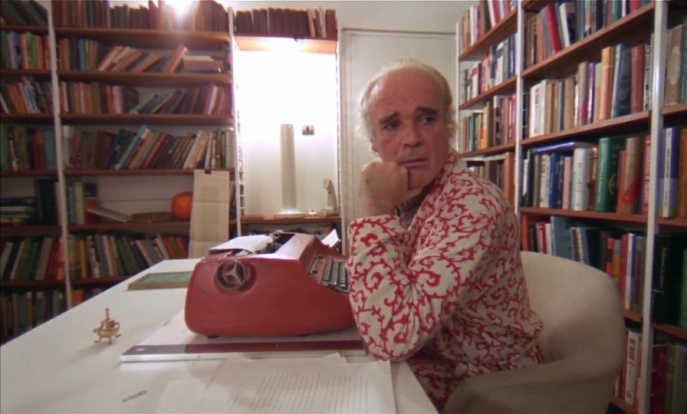

THE WRITER – Alex and the writer share the same name. The writer is called Mr. Alexander (PATRICK MAGEE). He wears a unique dressing gown when Alex bursts into his home and rapes his wife. Alex is wearing that same gown in the third act of the movie.

Furthermore, both own the same kind of bizarrely shaped telephone.

Fairly visible is also that both Mr. Alexander and Alex use a typewriter with exactly the same red color.

A giant light bulb is placed over the bed inside Alex’s bedroom, which corresponds to the giant light bulb in the writer’s bathroom just above the bathtub. The tub and the bulb are the same size as the bed and the bulb above.

THE CAT LADY – When Alex breaks into the house of the Cat Lady (MIRIAM KARLIN), he sees giant sexual paintings plastered all over the room.

The artist of these paintings is CORNELIS MAKKINK. He also painted the sexual painting in Alex’s bedroom.

The furniture inside the Korova bar where the gang hangs out is drowning with naked porcelain women’s bodies. To give light to the scene many light bulb decorations are used. That same kind of light bulb is used as decoration in the Cat Lady’s room.

The painting on the right side of the Cat Lady’s room shows a woman in bondages with the clothes cut out to reveal the breast, in the same fashion that Alex cuts the writer’s wife’s clothes before he violates her.

The chair in which the writer’s wife sat has the shape of a female breast and it also has an open hatch to foreshadow Alex’s cuts on the woman’s clothes.

MR DELTOID – An alternative poster for A Clockwork Orange shows Alex with a glass filled with dentures in front of his face.

The only person inside the movie who has any kind of contact with dentures is Mr. Deltoid (AUBREY MORRIS). By connecting these two characters through the glass, it serves as further evidence that Alex created other characters in the movie. Additionally, the alternative poster with fake teeth and an ironic smile suggests that Alex is lying in the film.

THE CHIEF GUARD – The guard in the prison not only looks like Hitler, but he speaks and moves like him.

The connection between Alex and the Chief Guard is further stated when the Chief Guard delivers Alex for the Ludovico Therapy. The Guard marches to the desk and jumps up to stop. Alex repeats the same action when asked to step to the front of the desk.

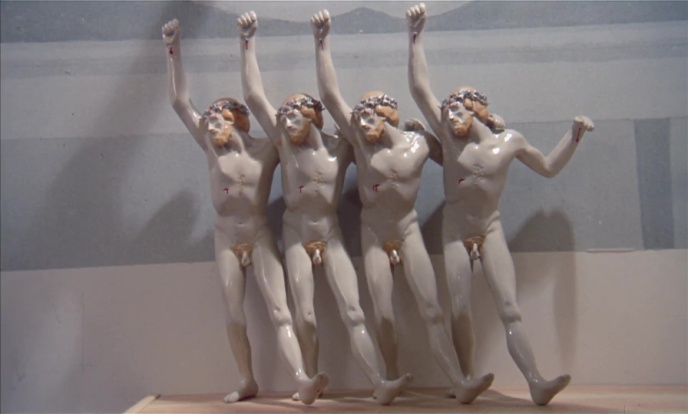

THE DROOGS – On the drawer of Alex’s bedroom nightstand are four identical small Jesus statues connected to each other, who bleed at the wrists. They represent the droogs.

All four are dressed in shabby white clothes and have fake bleeding eyeballs at their wrists acting as buttons to close the shirt. One Jesus is basically replicated four times, indicating how the droogs are not four individuals, but just that one – Alex.

- COINCIDENCES

In the first half of the film, Alex encounters a number of people for the first time, in the second half he is in prison, but in the third half, he is out of prison and encounters the same people from the first half of the film. Coincidence? Rather not. This kind of story structure leans toward classic movies like IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE (FRANK CAPRA, 1946.) or A CHRISTMAS CAROL (EDWIN L. MARIN, 1938.). The main character does many wrongs, which he is able to straighten out in the third act. He has to meet the same people in order to redeem himself. Alex didn’t encounter any new people in the third act except the ones he tortured or completely neglected.

From millions of music pieces that exist in the world, the scientists picked the one Alex adores for the Ludovico therapy. There is no other piece that should have been used since Alex revels in it so much that it creates fantasies about destruction in his mind. If the Ludovico therapy has to erase all traces of violence and sex, it is clear Beethoven needs to be erased as well. Assuming the therapy did go as planned, the writer, looking like Ludwig Van Beethoven himself, took revenge on Alex in the form of playing the music Alex could no longer enjoy. ‘Beethoven’ revenged himself, because Alex denied his music. The writer’s doorbell is also a clue worth considering. When rang, it plays a few notes from the beginning of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

Besides, a clever coincidence depicts basically two identical shots. One shot shows the scene where the writer executes his revenge by playing Beethoven’s 9th Symphony for Alex to drive him mad. The record player is placed in the middle of the frame with two black speakers placed on a billiard table left and right, and there are two additional gigantic black speakers placed behind the billiard table. This shot corresponds with the scene in the hospital at the end of the movie with the point of view of Alex, looking at the crowd that brought a record player and two gigantic brown speakers on the left and right side that blast Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. These shots represent opposites. The one with the writer is grim and claustrophobic, while the one in the hospital is well-lit and spacious, representing the positive state of mind and thus making the former shot an exhibit of the negative state of mind.

- ARCHITECTURE

What better setting could Kubrick choose to reflect Alex’s sick and perverted urges than an architecture movement by the name of Brutalist Architecture. It is the perfect fit,

‘sometimes abstract and almost always metaphoric sets’. (Kolker, 2003., 30)

These buildings don’t look run down like something from the past, but they also don’t look slick and high-tech like something that is connected to the future. They seem too heavy and extremely cold, too geometrical and it seems not much sunlight can pour through the windows. This kind of

‘Brutalism, more properly known as ‘New Brutalism’ in its heyday, is arguably one of the most unpopular and least understood architectural styles of the 20th century. It is mostly associated with rough-cast concrete buildings where its name is linked with the ‘beton brut’ casting technique used by le Corbusier’. (Yuill, 2004.)

Additionally, a helicopter gets a high-angle shot of the prison in which Alex is incarcerated.

It shows the prison from very much every angle to examine its layout, and a large green playground is visible, with criminals walking in circles.

Then the view cuts inside the prison, where Alex and similar criminals walk around an extremely small and literal white circle, which can’t exist since the audience already had the chance to inspect the layout from the scene before. The circle motif is used a lot in the film, mostly metaphorically, because it is connected to the overall theme. At the beginning of the story, Alex is a maniac with dangerous impulses. He is brought to prison where he undergoes the Ludovico therapy which erases his will to do evil completely, only for the government to reverse the process and bring him to the status quo again by the end of the movie. Other circular motifs include the eyeball on Alex’s shirt, the light bulbs inside the Korova bar, also the bulb in his bedroom, the circle-like architecture of the record shop, the glass table where Alex is dining with the writer, and so on. The motif is very prominent because it equals the Clockwork Orange metaphor.

- DURANGO 95

Alex called the car Durango 95 in the movie, but it’s a fabrication. The real name of the car is Adams Probe 16.

The design of the car looks like it’s been designed by an expressionist artist, but

‘It was stated by the designer that the shape of the car was inspired that of the female form, […] The design of the car from the A-pillars back was said by Adams to be inspired by a woman’s waist and buttocks‘. (Joseph, 2013)

Unfortunately, the car didn’t have a moment to really shine, but for the amount of time it was in the film it really merged with the overall aesthetic of the movie. The car scene was filmed with a background projection, clearly giving away its fake moment. The quote really sums it up, about the car being inspired by female curves. Every little detail connects to Alex’s sexual ambitions.

MYSTERY STILL UNSOLVED

With this amount of evidence, it should be clear that Kubrick tried to deliver a film that is devoid of morality, with an encapsulated timeless story, so it would entice audiences to make up their own minds about the problems our world is facing. As everything is played out in Alex’s mind, one big question remains. Who is Alex in reality? Since A Clockwork Orange is just the reflection of Alex’s psyche, can it be traced back to eventually getting an answer about his real personality? In the film his parents abandoned him, his friends betrayed him, his sexual outrage is woven through every thread of his existence and he is desperate for attention. These emotional blows could be echoes of reality that are hidden deep in the dark corners of his subconscious.

FINAL WORD

For decades spectators took everything the film presented for granted, never doubting whether they’ve been manipulated, or lied to, or that they went through the same journey the main character went through. There is simply too much evidence that Kubrick created more exciting layers of meaning on top of the basic story from the book. With the additional layers, he altered the meaning of the circumstances, leaving the core theme of the book intact. This film, like many others from his filmography, is the reason why he is hailed as a visionary and an extraordinary filmmaker. Almost sixty years later, his movie is still relevant and even today new layers emerge to be solved, to be analyzed, and to be appreciated.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bordwell, David; Thompson Kirstin, Film History: An introduction, McGraw Hill Higher Education, 2003.

Bordwell, David, ‘Graphic content ahead’, http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2011/05/25/graphic-content-ahead/, 2011.

Candna, Rishi, ‘Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange: The language within the language’, Mudra Institute of Communications, Ahmedabad, 2006.

Eisner, Lotte H., L’ EcranDemoniaque, Le Terrain Vague, 1952.

Falsetto, Mario, ‘Stanley Kubrick – A Narrative and Stylistic Analysis, Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data, 2001.

Joseph, Jacob, ‘Sexualized Cars: Adams Probe 16’, https://carbuzz.com/news/sexualized-cars-adams-probe-16, 2013.

Kubrick, Stanley, A Clockwork Orange, Warner Bros., 1971.

Kubrick quoted in Craig McGregor, ‘Nice boy from Bronx?’, New York Times, 30.1.1972.

McDougal, Stuart Y., Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, The Cambridge University Press Film Handbook Series, 2003.

Rice, Julian, Kubrick’s Hope – Discovering optimism from 2001 to Eyes Wide Shut, The Scarecrow Press, 2008.

Sinnerbrink, Trahair Lisa, Film and/as Ethics, SubStance #141, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2016.

Walker, Beverly, ‘From Novel to Film’ Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, Woman and Film 2, 1972.

Wolf, Norbert, Expressionism – Taschen Art Book, TaschenGmBH, 2004.

Yuill Simon, Code Art Brutalism, Software Art and Cultures, Digital Aesthetics Research Centre: Aarhus, 2004.